Get new exclusive access to healthcare business reports & breaking news

Verily, Alphabet’s life sciences subdivision, has announced that it is shelving a project to develop a contact lens that would have been able to measure glucose levels in tears.

Along with its partners, Novartis’ eye-care division and Alcon, Verily said in a blog post that they had decided to cancel the glucose-sensing lens, because it proved too difficult to obtain accurate glucose readings from tears.

Verily’s chief technical officer, Brian Otis explained that clinical work on the glucose-sensing lens had shown sufficient inconsistency in “our measurements of the correlation between tear glucose and blood glucose concentrations to support the requirements of a medical device. In part, this was associated with the challenges of obtaining reliable tear glucose readings in the complex on-eye environment.”

Otis said they had found interference from biomolecules in tears, which made it difficult to obtain accurate glucose readings from the small quantities of glucose in the tear film and that clinical studies had also demonstrated “challenges in achieving the steady state conditions necessary for reliable tear glucose readings.”

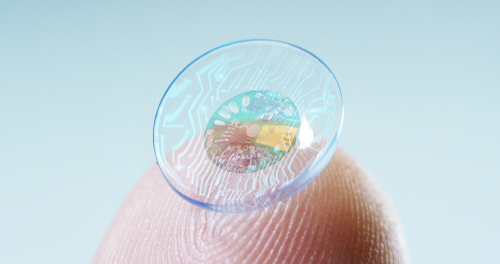

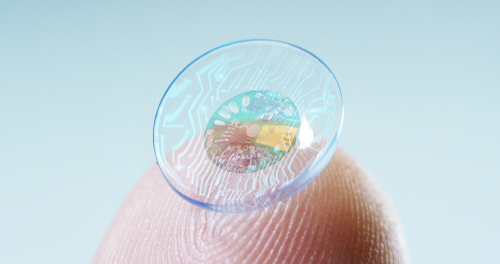

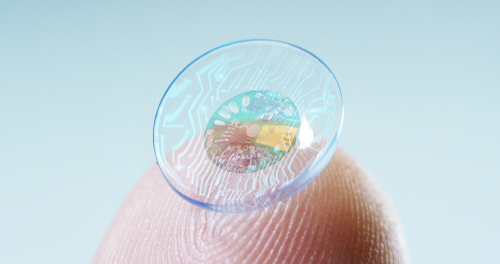

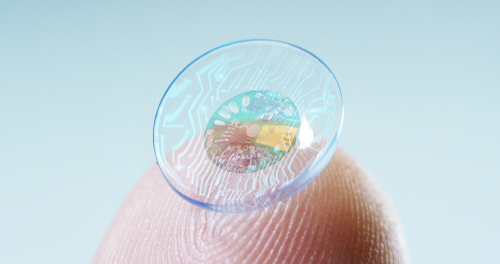

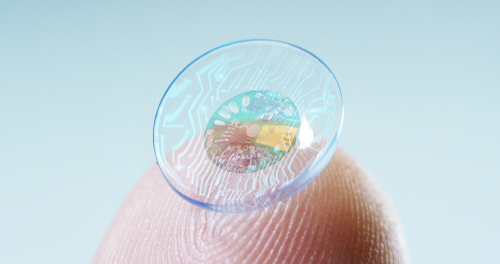

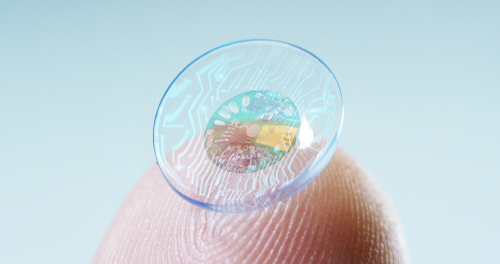

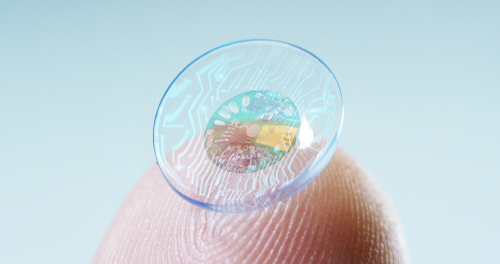

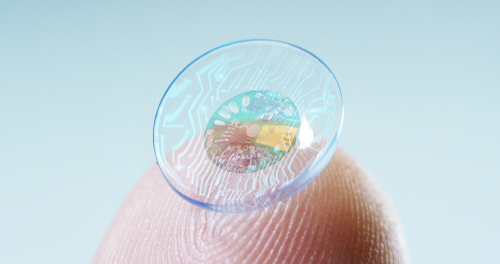

Had the project been successful, it would have helped diabetics better manage their blood sugar levels, since it would have worked by embedding sensors on a contact lens to monitor the glucose levels in their tears.

Verily, which was then known as Google Life Sciences, launched the smart lens project in 2014, in a effort to provide a less invasive way of measuring and tracking glucose levels. Traditional glucose meters use needles and Verily’s smart lens could have been a breakthrough in inobtrusive tech.

The shelving of the smart lens project marks an inglorious end for the glucose-sensing lens that was launched with a splash, despite warnings from experts that it was unlikely to succeed.

Experts had warned that tears are an unreliable measure of blood glucose, with The Verge quoting John L. Smith, a former chief scientific officer at Johnson & Johnson’s glucose monitoring division, who cautioned that “tears simply [do not] track closely enough with glucose in the blood.”

Glucose is notoriously hard to detect, experts warned, because it does not have distinguishing features and the body does not have much of it.

In 2016, when the STAT News website polled researchers, many were skeptical about the glucose-sensing lens, warning that “the quest to develop such contacts [was] technically infeasible because tears are an unreliable fluid to use in measuring blood sugar.”

By early 2017, the glucose-sensing device was running behind schedule, with trials in patients yet to begin. At the time,, Novartis only said the lens was a complex device and it did not know when patient trials were likely to commence.

In the face of early criticism that its innovation was likely to fail, Verily said: “As with all true innovation, some projects can and will fail.”

Despite the failure of the glucose-sensing lens, Verily insists their work was not in vain because the project had evolved into a “versatile electronics platform that can support actions, like sensing and transmitting data, on the eye.”

Verily said it was now working on a smart accommodating contact lens for presbyopia, a condition where the eye loses near focusing ability due to ageing. Verily is also working on a smart intraocular lens for improving sight following cataract surgery.

Otis said Verily had performed many clinical study sessions with individual users, collecting hundreds of thousands of biological data points from on-eye readings.

In addition, Verily said they were committed to improving the lives of people with diabetes through “improved methods for inexpensive and unobtrusive glucose sensing to support diabetes management.”

Verily said it was working with Dexcom to develop miniaturized continuous glucose monitors and with Onduo, its joint venture with Sanofi, to integrate continuous sensing into the care paradigm for people living with Type 2 diabetes.

In 2017, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said more than 100 million American adults were living with diabetes or prediabetes. Diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2015. It is estimated that by 2045, 692 million people worldwide will have diabetes.

With so many people affected by diabetes, a non-intrusive glucose monitoring device is considered a game changer. The drive to accomplish this has seen companies such as Alphabet and Apple investing heavily in the development of non-invasive devices.